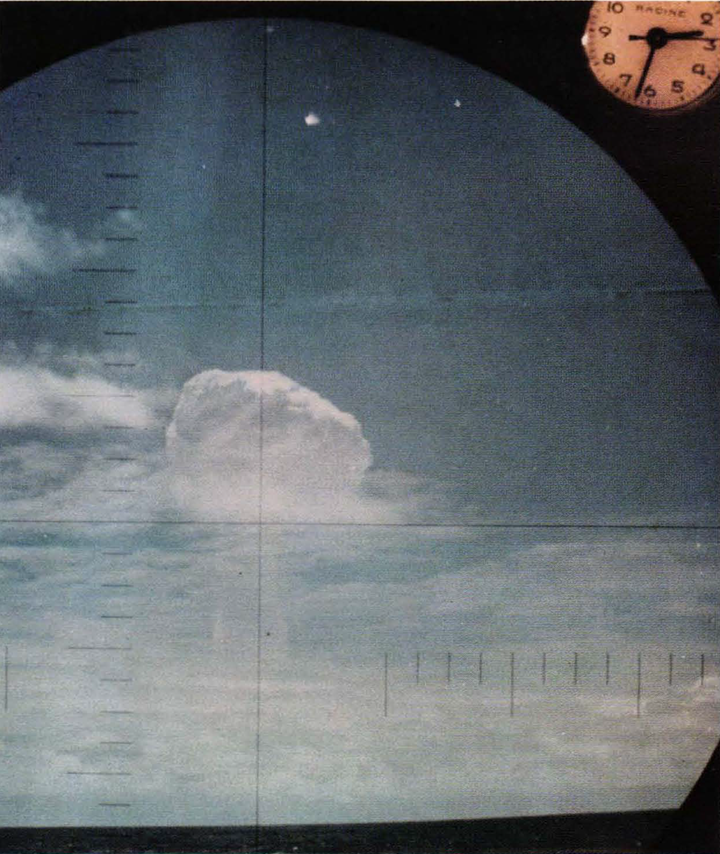

inevitable by choice – mad

Confirmation of a successful end-to-end flight test of Polaris (Operation Frigate Bird, 6 May 1962). The mushroom cloud from the Polaris warhead detonation is viewed through the periscope of a submarine in the vicinity of the target. This is the only complete test of a U.S. nuclear ballistic missile weapon. Source: Watson, J.M. (1992). Strategic missile submarine force and APL’s role in its development. Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, 13(1), 125-137.

Gwynne Dyer on the inevitability of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction):

Nothing is inevitable until it has actually happened, but the final war is undeniably a possibility and there is one statistical certainty. Any event that has a definite probability , however small, that does not decrease with time will eventually occur – next year, next decade, next century, but it will come. Including nuclear war.

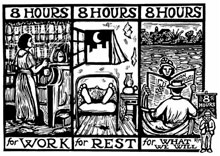

Only in this century have large numbers of people begun to question the basic assumptions of civilized societies about the usefulness and inevitability of war, as two mutually reinforcing trends have gained strength. One is moral: for all the atrocities we still practice on each other, the people the twentieth century are nevertheless more able than their ancestors to imagine that war – that is, killing foreigners for political reasons – may be simply wrong. The same great changes in society that have made war so lethal have also enabled us to see broader categories of people – even those on the far side of the nuclear palisade – as being essentially human beings like ourselves. And even if morality is no more than the rules we have made up for ourselves as we go along, one of those rules has always been that killing people is wrong.

The other fact is severely practical: we will almost all die, and our civilization with us, if we continue to practice war. A civilization confronted with the prospect of a “nuclear winter” does not need moral incentives to reconsider the value of the institution of war; it must change or perish.

Gwynne Dyer, War, 1985

perspective – making sense of modern landscapes

Charlotte Street, South Bronx, 1979

The city magnifies, spreads out, and advertises human nature in all its various manifestations. It is this that makes the city interesting, even fascinating. It is this, however, that makes it of all places the one in which to discover the secrets of human hearts, and to study human nature and society.

Robert Park

The City as a Social Laboratory

One day I walked with one of these middle-class gentlemen into Manchester. I spoke to him about the disgraceful unhealthy slums and drew his attention to the disgusting condition of that part of the town in which the factory workers lived. I declared that I had never seen so badly built a town in my life. He listened patiently and at the corner of the street at which we parted company, he remarked: "And yet there is a great deal of money made here. Good Morning, Sir."

Friedrich Engels

The Condition of the Working Class in England

…like the moon now, nothing but minerals…the buildings that used to form cliffs …had collapsed. Their wood had been consumed, and their stones had crashed down, had tumbled against one another until they locked at last in low and graceful curves. …walls still stood, but … windows and roof were gone, and there was nothing inside but ashes and dollops of melted glass. “It was like the moon,” said Billy Pilgrim.

Kurt Vonnegut

Slaughterhouse-Five

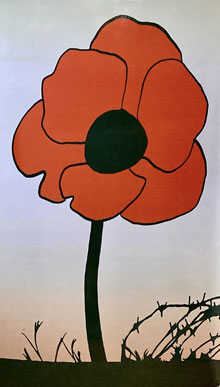

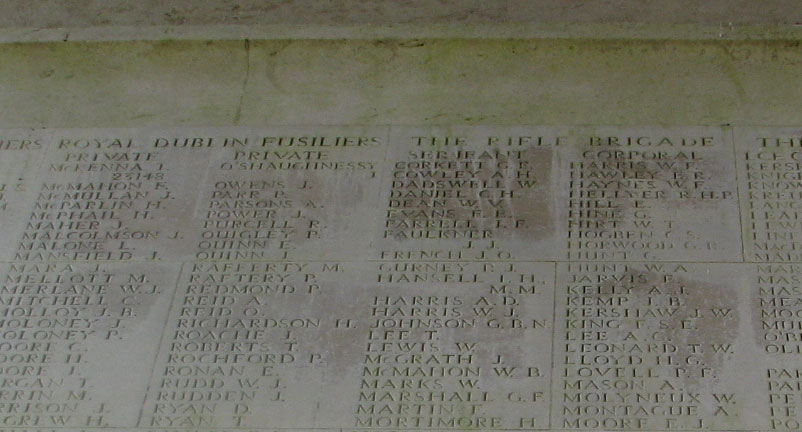

remembrance – absolution through accountancy

Photo: Katie Breslin, Thiepval Memorial

As I approach the Thiepval arch over a putting-green lawn, it occurs to me that the thing looks like a huge horseshoe magnet, held forever to the earth by the attraction of a million skeletons. (It is now estimated that there were 1,300,000 Allied and German casualties on the Somme in 1916.) In its central arch and numerous bays, there is the familiar sight of names upon names upon names, the ledgers of vertigo drawn up by a shamefaced establishment. Here, the stone letters spell out the names of the doomed soldiers of the British and South African armies (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Newfoundland, and India built their own monuments to the missing) who died on the Somme in the years 1915-17 and whose bodies were never recovered or identified. There are 73,412 of them. The memorial’s inscription reads, “The Missing of the Somme”; it could jusst as well say the sum of the missing. The magnitude of the number is too large to comprehend, just as at the Menin Gate. Like there too, the trick of absolution through accountancy is attempted – only here it works. The spectator, lone and vulnerable on the Thiepval ridge, feels oppressed by the weight of the engraved stone, as if it got there through some insensate natural force, ordained by an unkind universe rather than by the blunders of the powerful.

Stephen O’Shea, Back to the Front