assessing drug harms and drug facts

From the National Institute on Drug Abuse website

tobacco-nicotine

Brief Description

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of disease, disability, and death in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), cigarette smoking results in more than 480,000 premature deaths in the United States each year—about 1 in every 5 U.S. deaths1—and an additional 16 million people suffer with a serious illness caused by smoking.1 In fact,, for every one person who dies from smoking, about 30 more suffer from at least one serious tobacco-related illness.1

Revised August 2015

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of disease, disability, and death in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), cigarette smoking results in more than 480,000 premature deaths in the United States each year—about 1 in every 5 U.S. deaths—and an additional 16 million people suffer with a serious illness caused by smoking. In fact, for every one person who dies from smoking, about 30 more suffer from at least one serious tobacco-related illness.1

The harmful effects of smoking extend far beyond the smoker. Exposure to secondhand smoke can cause serious diseases and death. Each year, an estimated 88 million nonsmoking Americans are regularly exposed to secondhand smoke and almost 41,000 nonsmokers die from diseases caused by secondhand smoke exposure.1-2

How Does Tobacco Affect the Brain?

Cigarettes and other forms of tobacco—including cigars, pipe tobacco, snuff, and chewing tobacco—contain the addictive drug nicotine. Nicotine is readily absorbed into the bloodstream when a tobacco product is chewed, inhaled, or smoked. A typical smoker will take 10 puffs on a cigarette over the period of about 5 minutes that the cigarette is lit. Thus, a person who smokes about 1 pack (25 cigarettes) daily gets 250 “hits” of nicotine each day.

Upon entering the bloodstream, nicotine immediately stimulates the adrenal glands to release the hormone epinephrine (adrenaline). Epinephrine stimulates the central nervous system and increases blood pressure, respiration, and heart rate.

Similar to other addictive drugs like cocaine and heroin, nicotine increases levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which affects the brain pathways that control reward and pleasure. For many tobacco users, long-term brain changes induced by continued nicotine exposure result in addiction—a condition of compulsive drug seeking and use, even in the face of negative consequences. Studies suggest that additional compounds in tobacco smoke, such as acetaldehyde, may enhance nicotine’s effects on the brain.3

When an addicted user tries to quit, he or she experiences withdrawal symptoms including irritability, attention difficulties, sleep disturbances, increased appetite, and powerful cravings for tobacco. Treatments can help smokers manage these symptoms and improve the likelihood of successfully quitting.

What Other Adverse Effects Does Tobacco Have on Health?

Cigarette smoking accounts for about one-third of all cancers, including 90 percent of lung cancer cases. Smokeless tobacco (such as chewing tobacco and snuff) also increases the risk of cancer, especially oral cancers. In addition to cancer, smoking causes lung diseases such as chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and increases the risk of heart disease, including stroke, heart attack, vascular disease, and aneurysm. Smoking has also been linked to leukemia, cataracts, and pneumonia.4-5 On average, adults who smoke die 10 years earlier than nonsmokers.1

Although nicotine is addictive and can be toxic if ingested in high doses, it does not cause cancer—other chemicals are responsible for most of the severe health consequences of tobacco use. Tobacco smoke is a complex mixture of chemicals such as carbon monoxide, tar, formaldehyde, cyanide, and ammonia—many of which are known carcinogens. Carbon monoxide increases the chance of cardiovascular diseases. Tar exposes the user to an increased risk of lung cancer, emphysema, and bronchial disorders.

Pregnant women who smoke cigarettes run an increased risk of miscarriage, stillborn or premature infants, or infants with low birthweight.5 Maternal smoking may also be associated with learning and behavioral problems in children. Smoking more than one pack of cigarettes per day during pregnancy nearly doubles the risk that the affected child will become addicted to tobacco if that child starts smoking.6

While we often think of medical consequences that result from direct use of tobacco products, passive or secondary smoke also increases the risk for many diseases. Secondhand smoke, also known as environmental tobacco smoke, consists of exhaled smoke and smoke given off by the burning end of tobacco products.

Nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke at home or work increase their risk of developing heart disease by 25–30 percent and lung cancer by 20–30 percent.7 In addition; secondhand smoke causes health problems in both adults and children, such as coughing, overproduction of phlegm, reduced lung function and respiratory infections, including pneumonia and bronchitis.. Each year about 150,000 – 300,000 children younger than 18 months old experience respiratory tract infections caused by secondhand smoke.7 Children exposed to secondhand smoke are at an increased risk of ear infections, severe asthma, respiratory infections and death. In fact, more than 100,000 babies have died in the past 50 years from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and other health complications as a result of parental smoking.8 Children who grow up with parents who smoke are more likely to become smokers, thus placing themselves (and their future families) at risk for the same health problems as their parents when they become adults.

Although quitting can be difficult, the health benefits of smoking cessation are immediate and substantial—including reduced risk for cancers, heart disease, and stroke. A 35-year-old man who quits smoking will, on average, increase his life expectancy by 5 years.9

Are There Effective Treatments for Tobacco Addiction?

Tobacco addiction is a chronic disease that often requires multiple attempts to quit. Although some smokers are able to quit without help, many others need assistance. Both behavioral interventions (counseling) and medication can help smokers quit; but the combination of medication with counseling is more effective than either alone.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) has established a national toll-free quitline, 800-QUIT-NOW, to serve as an access point for any smoker seeking information and assistance in quitting. NIDA’s scientists are looking at ways to make smoking cessation easier by developing tools to make behavioral support available over the internet or through text-based messaging. In addition, NIDA is developing strategies designed to help vulnerable or hard-to-reach populations quit smoking.

Behavioral Treatments

Behavioral treatments employ a variety of methods to help smokers quit, ranging from self-help materials to counseling. These interventions teach people to recognize high-risk situations and develop coping strategies to deal with them.

Nicotine Replacement Treatments

Nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) were the first pharmacological treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in smoking cessation therapy. Current FDA-approved NRT products include nicotine chewing gum, the nicotine transdermal patch, nasal sprays, inhalers, and lozenges. NRTs deliver a controlled dose of nicotine to a smoker in order to relieve withdrawal symptoms during the smoking cessation process. They are most successful when used in combination with behavioral treatments.

Other Medications

Bupropion and varenicline are two FDA-approved non-nicotine medications that have helped people quit smoking. Bupropion, a medication that goes by the trade name Zyban, was approved by the FDA in 1997, and Varenicline tartrate (trade name: Chantix) was approved in 2006. It targets nicotine receptors in the brain, easing withdrawal symptoms and blocking the effects of nicotine if people resume smoking.

Current Treatment Research

Scientists are currently developing new smoking cessation therapies. For example, they are working on a nicotine vaccine, which would block nicotine’s reinforcing effects by causing the immune system to bind to nicotine in the bloodstream preventing it from reaching the brain. In addition, some medications already in use might work better if they are used together. Scientists are looking for ways to target several relapse symptoms at the same time—like withdrawal, craving and depression.

How Widespread Is Tobacco Use?

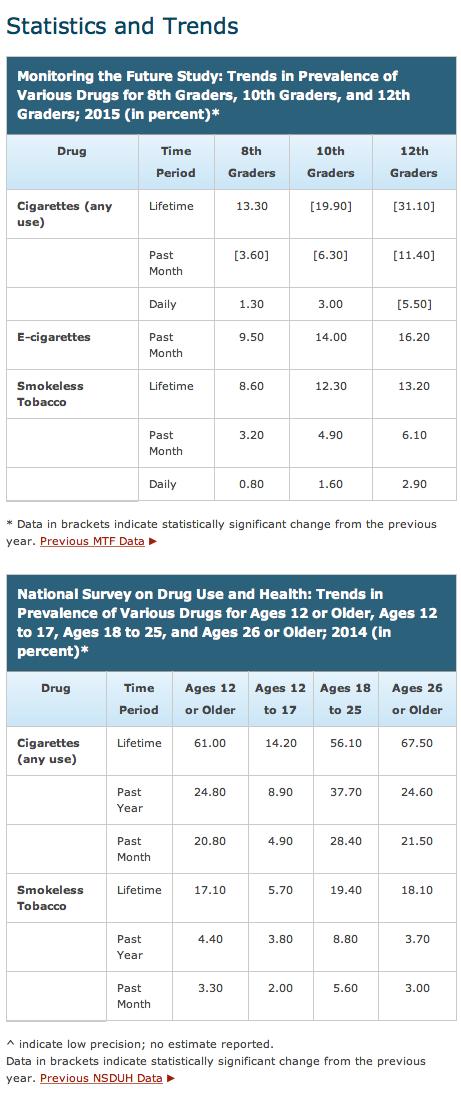

Monitoring the Future Survey*

Current smoking rates among 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students reached an all-time low in 2014. According to the Monitoring the Future survey, 4.0 percent of 8th-graders, 7.2 percent of 10th graders, and 13.6 percent of 12th-graders reported they had used cigarettes in the past month. Although unacceptably high numbers of youth continue to smoke, these numbers represent a significant decrease from peak smoking rates (21 percent in 8th-graders, 30 percent in 10th-graders, and 37 percent in 12th-graders) that were reached in the late 1990s.

The use of hookahs has also remained steady at high levels since its inclusion in the survey in 2010–past year use was reported by 22.9 percent of high school seniors. Meanwhile, past year use of small cigars has declined since 2010 yet remains high with 18.9 percent of 12th graders reporting past year use. Past-month use of smokeless tobacco in 2014 was reported by 3.0 percent of 8th graders, 5.3 percent of 10th graders, and 8.4 percent of 12th graders.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)**

In 2013, 25.5 percent of the U.S. population age 12 and older used a tobacco product at least once in the month prior to being interviewed. This figure includes 2 million young people aged 12 to 17 (7.8 percent of this age group). In addition, almost 55.8 million Americans (21.3 percent of the population) were current cigarette smokers; 12.4 million smoked cigars; more than 8.8 million used smokeless tobacco; and over 2.3 million smoked tobacco in pipes.

Learn More

For more information about how to quit smoking, visit: www.smokefree.gov

Data Sources

* These data are from the 2014 Monitoring the Future survey, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted annually by the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. The survey has tracked 12th-graders’ illicit drug use and related attitudes since 1975; in 1991, 8th- and 10th-graders were added to the study.

** NSDUH (formerly known as the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse) is an annual survey of Americans aged 12 and older conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This survey is available on line at www.samhsa.gov.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use: Fast Facts. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/

data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm#toll. Updated April 2014. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Nonsmokers' Exposure to Secondhand Smoke—United States, 1999-2008. MMWR. 2010;59(35):1141-1466. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5935a4.htm?s_cid=mm5935a4_w. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Cao J, Belluzzi JD, Loughlin SE, Keyler DE, Pentel PR, Leslie FM. Acetaldehyde, a major constituent of tobacco smoke, enhances behavioral, endocrine and neuronal responses to nicotine in adolescent and adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(9):2025-2035.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Health Consequences of Smoking: What It Means to You, 2004. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2004

/pdfs/whatitmeanstoyou.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use: Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/

health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm. Updated February 2014. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Buka SL, Shenassa ED, Niaura R. Elevated risk of tobacco dependence among offspring of mothers who smoked during pregnancy: A 30-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1978-1984.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use: Secondhand Smoke (SHS) Facts. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/

secondhand_smoke/general_facts/index.htm. Updated April 2014. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/index.htm. Published January 2014. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1990. HHS Publication No. 90-8416.

- Rigotti NA. e-Cigarette Use and Subsequent Tobacco Use by Adolescents: New Evidence About a Potential Risk of e-Cigarettes. JAMA. 2015;314(7):673-674.